Stop Doing Fragile Research

A few months into my PhD, I had my first original idea. The epiphany struck as I was biking down to my lab on a cold, sunny midmorning, and I remember almost shaking in my bike seat with excitement. As soon as I got to a computer, I opened up a python notebook and started typing. I pounded out the lines of code, nervously wondering whether the idea could really work. I generated some random data and simulated my method on the dataset.

A few seconds later, the simulation finished running and the result appeared as an accuracy underneath my code: 93%. It looked great! I pressed shift-ENTER to rerun the simulation with a new randomly-generated dataset. This time around, the results looked a lot worse. I ran the simulations a few more times, and the results seemed to be all over the place. In order to make the results a little bit better, I changed how I generated the data, reducing the dimensionality of my data and making the problem more tractable. This time around, the accuracies seemed to improve, and so I tweaked the data again. After a few tweaks, I was getting consistently good results, and so I started fantasizing about how I would present this to my advisor.

This story is familiar to anyone who works with data, runs simulations, or conducts experiments. If you have a novel method or hypothesis you want to test, you’re naturally eager to find confirmation through experiments and simulations. However, in doing so, you treat your method as fragile, carefully constructing the dataset or tuning the conditions to showcase your method in the best possible light. Rather than changing your method, you adapt the dataset. Furthermore, you run many experiments and (perhaps even subconsciously) focus on those trials that appear favorable. Our minds, naturally adept at recognizing patterns, associate positive trials with success and ignore or neglect those that don’t fit our mental expectations. When we have our final results, we forget all of the careful assumptions we’ve made and biases we’ve accumulated, and present our method in an unrealistic light.

I realized that I was making this mistake when I first showed my results to my colleague Jamal*. Let me provide some context: We were working on a new way to find patterns in high-dimensional data. Because humans can’t visualize high dimensions easily, pattern-finding techniques identify a 2-dimensional projection of the data and show the user that projection. The art (or the algorithm) is in finding the right projection, which reveals the clusters or other patterns hiding within the data. The simplest technique is known as PCA, and it selects as the projection the 2 dimensions with the most variation, since they are the most likely to contain patterns of interest. However, our insight was that we can choose a better projection by using information from a second, background dataset that does not have the patterns we’re looking for. We developed a method called contrastive PCA (details) to perform this analysis.

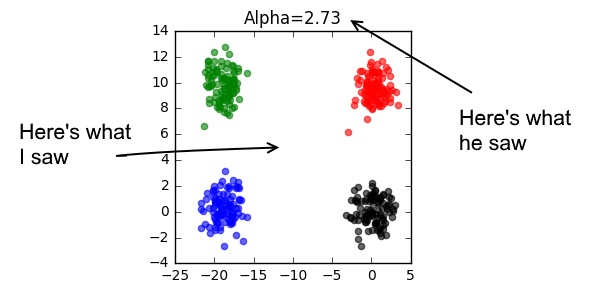

When I first ran contrastive PCA on a dataset, I generated a bunch of plots by tuning a parameter that I’ll call “alpha”. For one of the values of alpha, contrastive PCA found a projection of the data that beautifully separated the four clusters within the data. When I showed Jamal the figure, I thought he would be blown away. Instead, he skeptically waved his hands at my results. Here’s why:

“Why did you pick this value of alpha?” He asked, rightly pointing out that I had no a priori reason for picking this value of alpha. For all we knew, I might have gotten lucky, by choosing a parameter that just happened to work for this dataset. Imagine if values of alpha allowed me to cycle through every possible projection. It wouldn’t be a surprise if one of them happened to be the projection that separated the data points. Jamal also gave me some other advice: “Throw your research against the wall, because if you don’t, someone else will.”

In other words, don’t just look for datasets or settings that make your method work. Stress-test your work. When does it fail? Why? By asking these questions, you’ll have an unbiased understanding of the method. Over time, I’ve started doing certain things that I think have helped me get this clearer perspective. Here are three such things:

1. Run At Least 10 Simulations At Once, and Only Look at the Aggregate Results

The human mind is really good at finding patterns. Often times, we’ll run just one simulation at a time, and we’ll start to build a mental model of whether our method is working by looking at the results of the first few simulations or by a few simulations that are extremely good or dramatically bad. We might hallucinate patterns that really aren’t there. This is especially the case if you’re comparing your novel method with a standard baseline. If there’s variation in the results, often times, it can seem that your method is usually working better than the baseline when on average it isn’t.

To avoid making imaginary inferences, generate lots of random, independent datasets and run your method with all of them. Display aggregate results (such as means and standard deviations), and ideally plot the results. Graphs deceive less frequently than raw numbers.

If your method requires working with a real dataset that cannot be simulated, bootstrap your data: pick samples from your dataset (randomly, with replacement) to generate at least 10 new datasets of the same size as your original. Then, run the method across all bootstrapped data.

Do this from the very beginning: it may seem like extra work, but the payoff is that you won’t go bumbling down the wrong path.

2. Have a Negative Control Dataset

Let’s say that you have invented a new clustering technique. You generate a bunch of datasets with two clusters of points. As you bring the clusters closer and closer together, you observe that existing clustering techniques are unable to resolve the clusters in the data, but your technique continues to work. Success? Not so fast!

What if you are accidentally feeding the ground-truth labels into your clustering algorithm? (Embarrassingly, this happened to me once). To make sure your algorithm isn’t using information it shouldn’t have access to, or it isn’t too sensitive, or some other silly mistake, generate a negative control dataset, for example by generating the two clusters with identical distributions or by randomly shuffling the labels on a classification task.

Is your method still working on the negative control? If so, you have a problem.

3. Look Out for Free Parameters

As I mentioned earlier, you have to be particularly careful if your method has free (hyper)parameters. It’s easy to fool yourself into adjusting the hyperparameter just so until your method is working perfectly on a particular dataset. Then, when you try your method on a very different dataset, the algorithm fails worse than an old guitar as parameters need to be re-tuned.

To clarify, the mere presence of hyperparameters isn’t a problem. If you find that the algorithm isn’t too sensitive to the choice of parameters across its range of operation, then there’s nothing to worry about (take a look at t-SNE, for example). Even if the algorithm is sensitive to the parameters, but those parameters can be estimated from properties of the dataset, then you can build a subroutine that automatically chooses suitable values for hyperparameters. This is what we ended up doing for contrastive PCA.

In general, the point of this Rule is: adopt an antagonistic mindset when you’re doing research. At this risk of sounding extreme, try to get your method to fail. By finding the weak points of your algorithm or experiment, you’ll be forced to find ways to strengthen it and develop a method that is actually useful in the wild – that is, to other people who are using it outside the carefully curated conditions of your lab.

* Not his real name